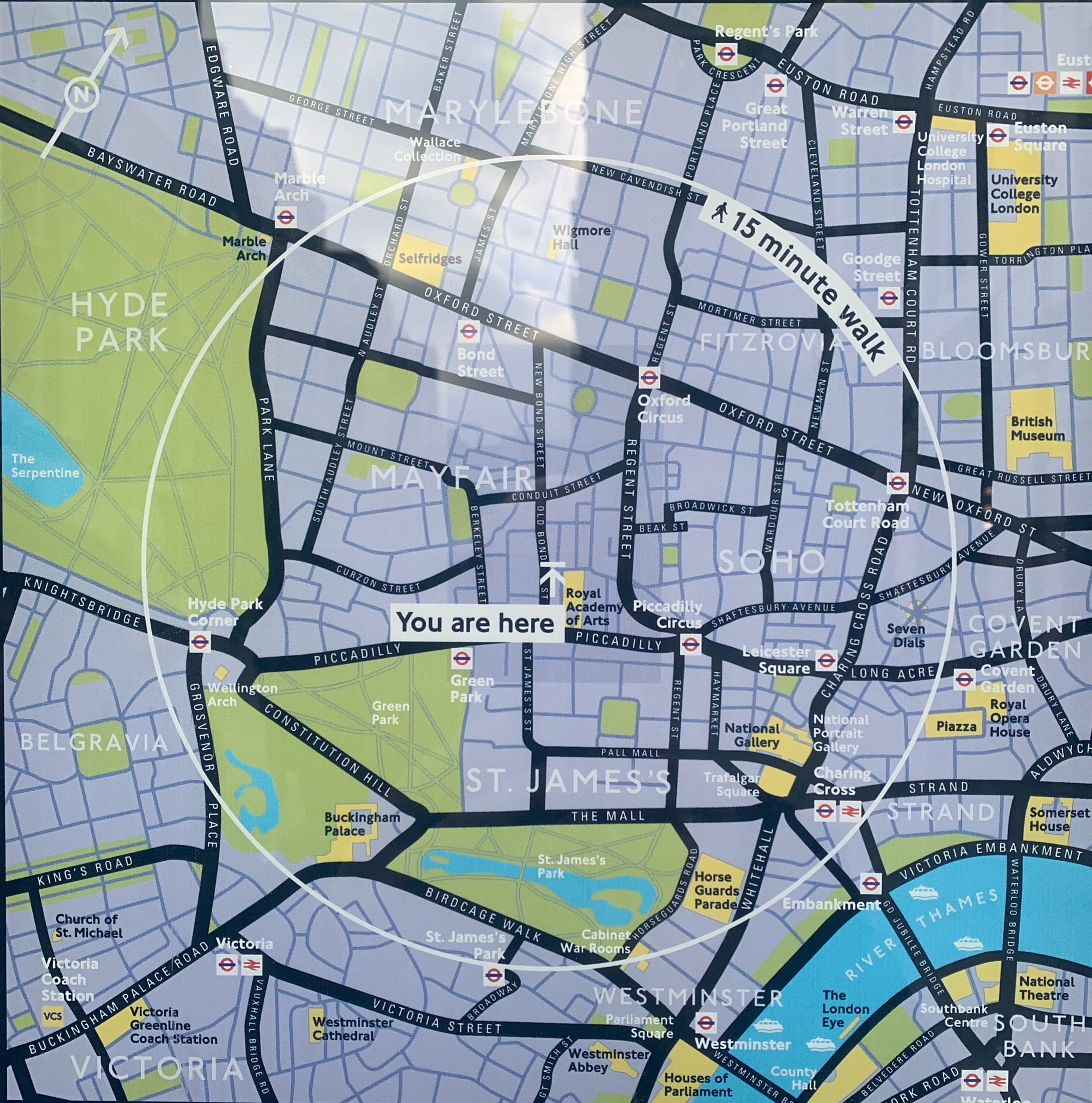

Many years ago, I swear, Private Eye reprinted without comment a map from another publication showing the major cities of Spain in accurate relation to each other – but overlaid on an outline that was clearly the shape of France. The Tribune has had its moments with maps over the years, but I’ve never seen us do anything like that. And I’ve never seen anything quite like this pair either, on a public information point in no less a thoroughfare than Old Bond Street.

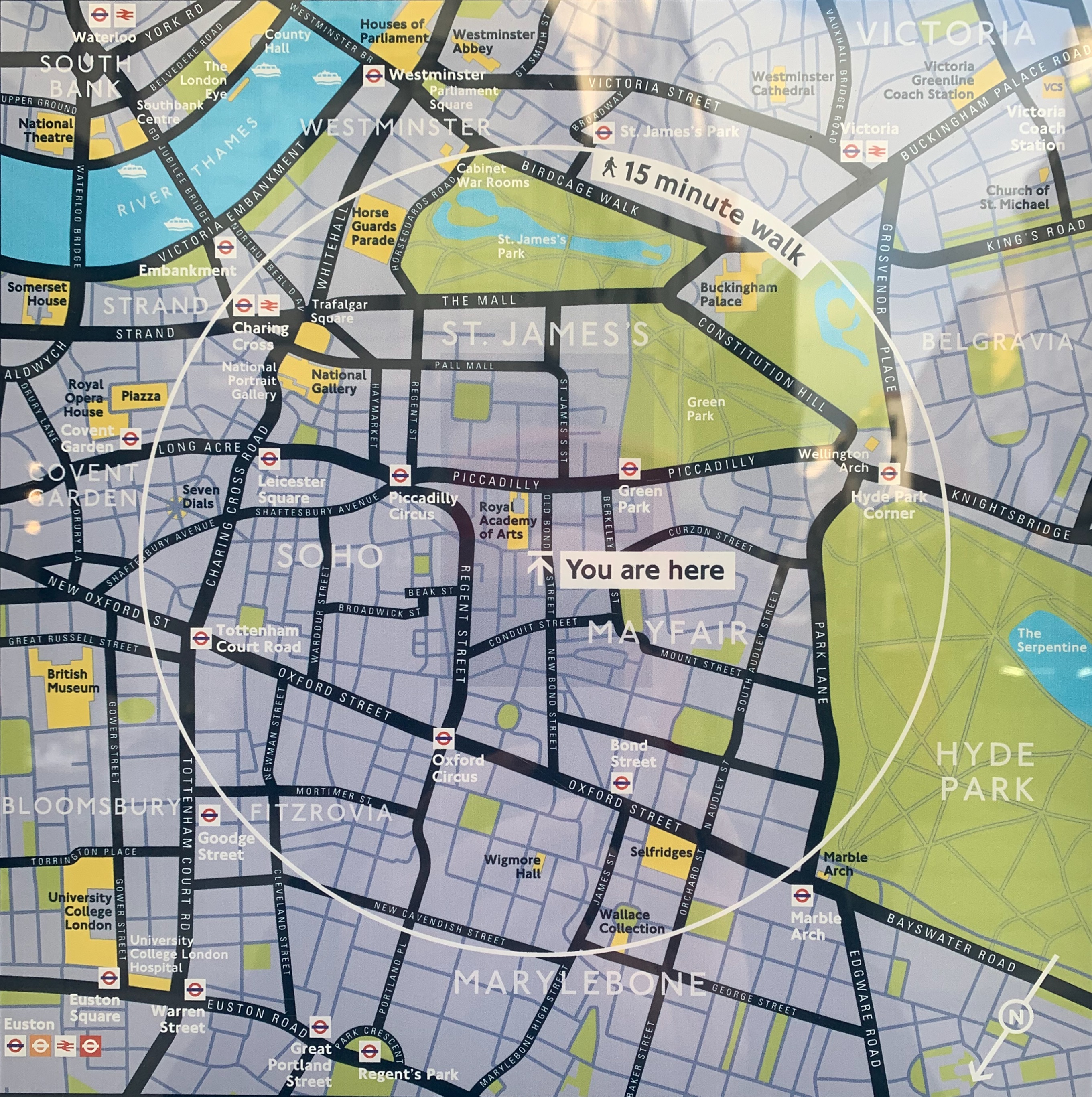

I was just passing on a meandering walk around the West End and stopped to look. The first map is a completely normal map of Mayfair for tourists. The second one, which was on the other side of the information point, is … well, I’m not quite sure what it is. I stared for a full minute trying to work out what I was looking at. Buckingham Palace seemed to be further south than Lambeth Palace. The South Bank was on the north bank. I had to walk round the sign and look at the first map again to realise what they had done: they’ve flipped the pictorial part of the map over while keeping the labels the same way up.

Now admittedly there is a discreet symbol on the bottom right showing that “North” is in what one would think of as a south-westerly direction, but is that what you would normally expect from a map like this – that visitors would have to mentally rotate it in the manner of a teenager doing a cognitive aptitude test? Taking it at face value, Hyde Park appears to be east of Mayfair, whereas of course it is west. If you glanced at this and set off using the position of the sun or your phone compass as a guide, you’d never find it. Even if you followed the street layout, you’d still start out the wrong way.

What could Westminster Council be thinking here? It threw me for a loop, and I was born in London and have lived here for the last 25 years. Imagine being a tourist and trying to work it out. I haven’t shown this to the Tribune’s graphics desk – who have been producing daily maps of the shifting tides of war in the Donbas with barely a mistake for 12 months – in case it distresses them. But this seems so finished, so “meant”, that I can’t shake the idea that I’m missing something, and that this is some known and legitimate form of map-making. I might get in touch with the council and see what they say – watch this space.

UPDATE: It has been patiently explained to the blog by its friends that of course the point of these maps is that they are “direction of travel” maps. I should have realised something like that by the fact that they were so different on opposite sides of the same signpost. The “upside down” map is for people walking in a southerly direction down Bond Street – it has been pre-rotated so that when you look at the map and then look up, you can see the street layout in front of you the way it’s drawn on the sign. I get it now! But just to make a few observations:

- Apart from the very discreet North orientation arrow on the maps, there is no obvious “you’re facing this way” indicator on the maps, leading to point two.

- What are your expectations of such maps? Mine would be that they would be simple north-at-the-top drawings in the context of public information points – the simple standard everyone would understand? But maybe that’s just me.

- This would probably have been less confusing (to me, anyway) if Bond Street didn’t run almost north-south. That means the northbound map looks deceptively like a simple north-is-up map (although in fact it isn’t).