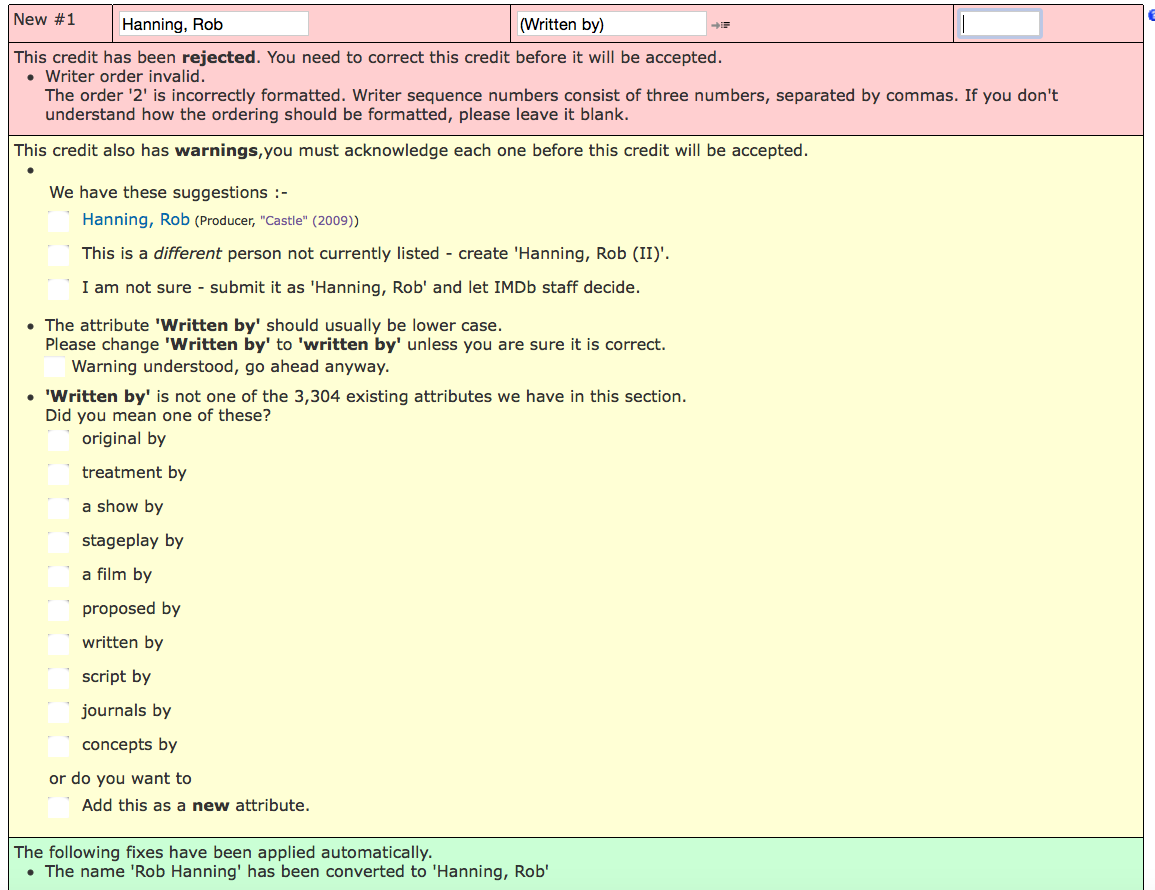

‘There’s bound to be a big replate for second edition’. (IMDB/BFI)

The street shimmers. A man trudges towards the camera through an apocalyptic glow, bathed in sweat. A tannoy announces there are “nineteen minutes before countdown” to a scorched, empty city. It looks like Doomsday, but all is not lost: because the man is a journalist, and he’s on his way to the newsroom.

And so begins The Day The Earth Caught Fire, Val Guest’s 1961 film with an exploitation-movie title that in fact manages to be a nuclear thriller, ecological parable and gritty love story all at once. And, almost above all, a film about newspapers.

It stars Edward Judd as washed-up reporter Pete Stenning, Leo McKern as grouchy science editor Bill Maguire, and Janet Munro as Jeannie Craig, a government press officer who knows a secret. The two male characters work at the Daily Express, whose newsroom was exactingly recreated at Shepperton Studios for the film. And although the story concerns America, Russia and the disastrous coincidence of two H-bomb tests, nearly everything that unfolds is viewed from the inside of a newsroom or a bar.

Scene after scene is heavy with the presence of midcentury Fleet Street. Billboards proclaiming disaster are displayed on Evening Standard vans. The wall of a lido where Stenning and Craig, his new girlfriend, meet is covered with a huge advert for the News of the World. The newsroom is led by a commanding Arthur Christiansen-type figure, played by … Arthur Christiansen himself, who was also the film’s technical adviser. It is a disaster movie, certainly, but it’s about the end of the world in the same oblique way that All The President’s Men is about Nixon.

And the hacks themselves are also very real. Messengers and copyboys are chaffed and ordered about. The troubled Stenning sulks and slacks off, and is confronted about it unsparingly by colleagues (“If you borrow my car for lunch, why bother to hurry back at six-thirty?”). When he gets a sniff of the climate-disaster story, he shows little compunction in forcing Craig, who works at the Air Ministry, to act as his source, exposing her to the fate of a whistleblower. The film was somewhat scandalous in 1961 for its frank love scene, but you suspect it got its X certificate not because of all the sex, but because of all the journalism.

In the opening scenes in the newsroom, as a flash comes in and a shocked desk realises what’s happened, we see a detailed recreation of a post-deadline panic. The news editor dials the switchboard: “Head Printer, fast!” Maguire reappears. “Give me a quick 50 words across three columns. You’ve got five minutes. I’ll write the headline.” The head printer picks up the phone. “Smudge: slip edition coming down in five minutes at most, so get a bloody move on!” (“Don’t we always?”).

Cut to the composing room, where the head printer calls out “front page lead reset!” and dials the press manager to tell him there’s a newsflash. (“OK George. Know what it is? Well as long as they haven’t made beer illegal!”). The press manager goes to the press foreman, and against the din of the machines, raises his index finger and makes an upward gesture, meaning “lift page 1”. Then he goes to the delivery manager to warn him “there’s bound to be a big replate for second edition”. (“Someone up there hates me! All right, I’ll warn them”). He dials the loading bay, where the first edition is being gathered and baled (and where we see Stenning, stumbling in after another lost afternoon, and follow him back up to the newsroom).

‘Why is he trying to alter my heading?’ (BFI)

It’s three minutes of tense Fleet Street life, a vivid glimpse behind the scenes – except that, as you might have noticed, it doesn’t appear to involve sub-editors. The news editor talks straight to the typesetters, writes the headline, and even organises the photographs (“Jock! Find me the biggest mushroom in the file!”). It’s possible that a busy news editor might take on the task of writing a stop-press headline, for speed, but in real life there would be upwards of a dozen subs around who could do it for him.

Fear not, though: in such an exactingly recreated newsroom, sub-editors are indeed present – pre-dating both their appearance in The Paper (1994) and The Post (2017). Earlier in the evening, we saw Maguire – who appears to be the kind of reporter who likes writing his own headlines – kicking up a fuss about changes to his feature on thrombosis. “But why’s he trying to alter my heading?”, he complains to a mild-looking middle-aged man, whose patient demeanour marks him out as a member of the copy desk. “Is he trying to make a job for himself?”

“Bill,” the man replies (with justification), “you can’t print a feature on thrombosis and call it YOU TOO CAN BE THE DEATH OF THE PARTY.”

And when the early copies of the first edition eventually arrive upstairs, Maguire is seen holding one aloft in disgust. “Eight hundred grisly words on thrombosis and look what they do to me: STUBBORN MEN AND THE KILLER THEY COURT. What kind of an impact heading is that? I might as well be working on the Police Gazette!”

I quite like it myself. But anyway, it didn’t matter: the whole thing got pulled for the second edition because the Earth had been blown off its axis.

Hat-tip to Theresa Pitt at Horny Handed Subs of Toil, who recommended the film to the group.

Tags: Hollywood, The Day The Earth Caught Fire