We used to be disciplined about this. For headlines, the rule was three and three in mobile view – that is to say, three decks of headline and three decks of standfirst, and no more, when looking at a Tribune article on your phone.

That’s pretty tight, so I used to allow myself to go three and four or four and three (OK, sometimes even four and four).

But now look what’s happened.

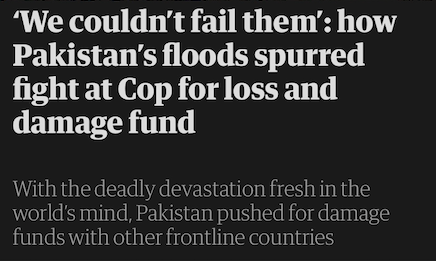

The Audience department has started brightly saying things like “it’s sometimes worth going slightly longer on a headline to add a kicker that punches up the drama!”. And with just that brief exposure to SEO radiation, the town’s gone crazy and giant monstrosities have BROKEN LOOSE.

Some of these headlines are literally double the height of what we restricted ourselves to in the old days. The thinking used to be that you would want a reader to see the whole headline and the standfirst, at least, on the same screen, to engage them before their attention wandered. Now you have to scroll just to get to the end of the first element. Long headlines may be able to punch up the drama, but perhaps not if you can’t read to the end of them on anything smaller than an iPad.

And that’s before you even consider the issue of the view in desktop mode. Many fewer people read the site on a computer than on a phone these days, so the rule is “make it look good on mobile”, but the appearance on the big screen still matters. The way the Tribune system is set up, there’s a sweet spot at about the three-and-four length that comes out neatly as two-and-two on desktop. There isn’t a built-in length guide in our software, but after a while you get used to hitting it, and making sacrifices to avoid creating, say, an orphan on a third deck. Now it seems they want us to pack the furniture with all the interest as well as the search terms, and hang the look or the length.

If you have any involvement in online media, you soon learn that search engine optimisation goes in phases. Pure SEO is, when you think about it, an unusual job – in effect, analysing and guessing how a private company’s proprietary algorithm might be working. Being a professional Google-watcher has its tribulations: for example, it used to be thought 15 years ago that repeating search terms in the headline and the standfirst was the key to being seen. Then it was thought that the standfirst might matter less for visibility than the main caption, and so on.

However, as the SEO role has expanded into what is now called “Audience”, it has engaged more widely with social media and news aggregator services, and is becoming – somewhat to sub-editors’ chagrin – a general headline-critiquing service in which social impact and readability are judged alongside search-friendliness. The rules are changing, again, and as one’s age and inflexibility increases, the harder it is to keep up.

On the other hand though, who’s to say they aren’t right about this? Which is the most successful British newspaper website of them all? Mail Online. And how long are Mail Online headlines? Well, er …

Eight decks, with an orphan. In desktop view! As well as a four-deck standfirst. It makes us look like amateurs. It also tramples all over the idea of brevity as a virtue in journalism: but maybe brevity was only a virtue when there was limited space, in the days of print? This is long, rambling and takes a whole breath to read out loud, but it contains every single likely search term relating to the story, and there is no shortage of space on the internet. Maybe length is not the issue at all any more. Maybe online visibility is the only thing that matters?

As the holidays approach, Ten Minutes Past Deadline has thrown some presents in the boot and is joining the queues on the M25 for its short peri-festivus break. Happy Christmas to all, and see you in the new year.