I regret to report that, after years with no serious incidents, someone has stumbled on to the biggest booby trap in the Tribune’s stylebook and set it off. A member of the newsdesk, having seen a piece on a Flemish master go up on the website, innocently emailed to say: “Hi, please can we commit to either Bruegel or Brueghel in this? We’ve got a bit of both at the moment.”

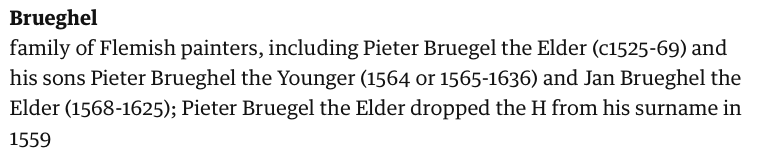

Well, experienced arts subs will know what is coming next. The web production editor did the kindest thing he could, which was simply to email the style guide entry to him without comment. It reads as follows:

Yes, indeed. It’s not just that the spellings are intrinsically tricky. It’s not just that there are two Pieters, the Elder and the Younger (as well as Jan, who although a son of the Elder, is also an Elder himself). It’s that the older one changed the spelling of the family name halfway through his life, but the younger one didn’t.

What chance do you have of deducing that if you don’t happen to know it? To my mind, following the inconsistency that the rule demands results in a gnomic hypercorrectness that baffles readers (and the newsdesk) – except that this is unquestionably what happened, as Brueg(h)el’s signed canvases testify. What to do instead? Are we going to call a Bruegel a Brueghel, when we would never dream of attributing a Jefferson Starship album to Jefferson Airplane?

It’s the only spelling I know that needs to be checked against a calendar as well as a biography, and that’s what puts it slightly ahead of the second biggest booby trap in the Tribune’s stylebook – the Lloyd Webber Rule.

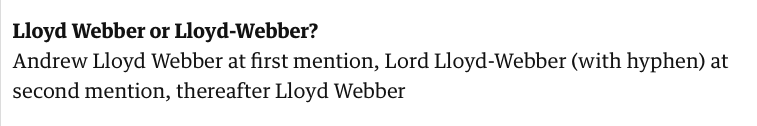

Andrew Lloyd Webber (thus, no hyphen) has a double-barrelled name. He was ennobled in 1997, and the rules of the House of Lords require that all compound names be hyphenated for the purposes of a title, whether they usually are or not. He is therefore, formally, Lord Lloyd-Webber of Sydmonton.

Also, strictly speaking, as all British sub-editors know, if you are using a lord or lady’s title you should not use their first name with it (so, eg, you say Lady Rendell or Ruth Rendell: not Lady Ruth Rendell).*

In that light, our style on peerages demands three things:

(i) That the peer in question be given their full name only at first mention, rather than their honorific, for absolute clarity of identification.

(ii) That the honorific then be given at second mention.

(iii) That, in the egalitarian spirit of the Tribune, all persons of voting age (with rare exceptions) be usually referred to by surname only, no matter how honoured they may be. This rule even applies to peers. So, for example, the correct style for Laurence Olivier would be Laurence Olivier, first mention; Lord Olivier, second mention; Olivier, third and subsequent mentions.

So if you put the House of Lords convention together with the Tribune’s style guide, you get the Lloyd Webber Rule:

Hyphenating an unhyphenated surname on second mention only? Now that’s what I call a rule.

*Unless they are the younger son of a duke or marquess, obviously! Ah, if only the Telegraph style guide were not now behind a paywall; what a guide that was to the minutiae of aristocratic convention.