Woe betide the editor who moves the crossword: this is an axiom you will hear repeated in the corridors of power at every British newspaper. Decades ago, the Tribune reprinted the entire leaked text of a speech by Khrushchev denouncing Stalinism; as well as being one of the most highbrow scoops in history, it also took up literally half the paper, displacing ads and other stories left and right. We asked the Tribune’s current editor whether he would consider doing the same today. He responded: “Can you imagine what the readers would say? ‘Where’s the quick crossword?'”

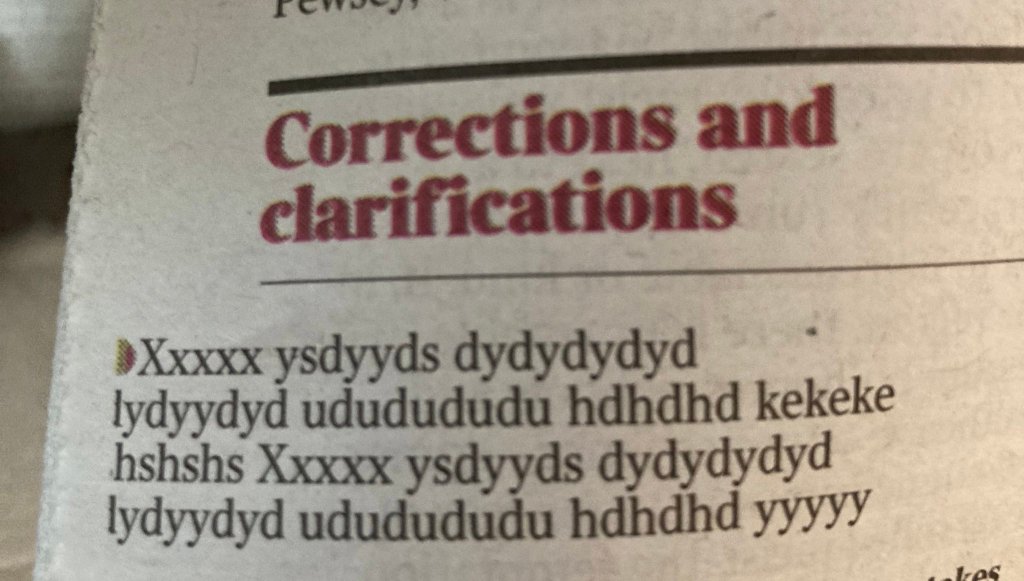

It is also a tense moment if there’s ever a mistake in a crossword clue, and I cringe in sympathy every time one appears in the corrections column. Puzzlers are a vocal and demanding clientele. But when this one appeared last week, I honestly couldn’t work out what was wrong:

Did you get the answer? I did, or I thought I did: the same for both clues. But do you see the reason for the correction? I could only assume it must have been a “tone” thing. Some objection to invoking Mrs Fawlty because of the resonance of Basil’s “yes, dear” disparagements? An unpalatable resonance of 70s sexism as entertainment? But no, it’s more simple and practical than that. It’s because, even though they derive from the same word, Sybil, as in Fawlty or Thorndike, is spelled Sybil, and sibyl, as in female Roman oracle, is spelled sibyl. The problem isn’t political correctness: it’s because spelling 18 across as the name makes it impossible to get 14 down (“Disgusting” (4 letters); answer: “icky”).

Sibyl, then, joins the (I like to think short) list of words I’m not quite sure how to spell. Bill Bryson tells the story that he got his job on the Times subs’ desk in London by correctly betting his interviewer that he was the only one in the building who could confidently spell “Cincinnati”. At one time, I couldn’t spell it either, but I’m there now, after diligent memorisation (one n, two n’s, one t). I can hope to do better in future this time too, if not actually prophesy it.

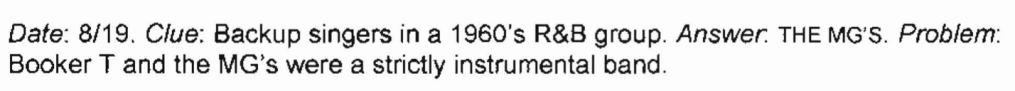

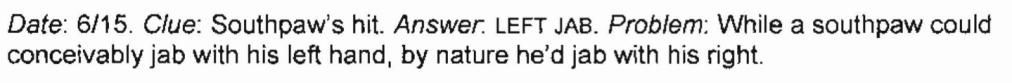

Also, googling round the subject seems to suggest that puzzle errors are not as rare as one might suppose. In 2006, the high-profile crossword editor of the New York Times, Will Shortz, published a list of all the mistakes that had appeared on his watch to that point (he started in 1993 and is still in the job today). Some of them are simple factual errors, but some of them are just the kind of semi-concealed mistakes that any sub-editor would be proud to spot. These two are my favourites:

Full list here. (I also enjoyed the tubular/cylindrical nit-pick, but that clue about the Uzi would be impossibly vague even if it were correct.)

More anon

20 FebThis blog has always had an eye for an odd correction, and this one certainly seems a bit odd:

As we were discussing last time, social media, and the anonymity it affords, is starting to have a noticeable influence on the tone of traditional journalism. One aspect of this is that news is starting to sound slightly less serious, as substantial stories are sourced from revelations published by Twitter users with silly names. But in another respect, the prevalence of pseudonyms on web platforms – including, in most cases, news organisations’ own sites – means that news is also becoming more profoundly anonymous.

Of course, this is hardly a new concept for journalism: some of the biggest stories ever broken have relied on unidentified informants, from Deep Throat to the person who sold MPs’ expenses data to the Telegraph. But in cases like those, although the reader did not know who the source was, the reporter did: and the organisation always had some opportunity to weigh up its informant’s bona fides. In the old days, anonymous sourcing worked because of an implicit assurance offered by the newspaper: we cannot name this person, but you can trust them because we trust them.

The crucial difference between then and now is that, in the case of an online commenter or social media user, it is not always possible to offer that assurance. Indeed, it is likely in many cases that nobody in the news organisation – not the journalists, and probably not even the website administrator – really knows who they’re dealing with. Typically, to log in to a newspaper website and make a comment, you need only give a name (not necessarily your own), an email address (not necessarily one that identifies you), and a date of birth, which hardly narrows things down. Everything you need to join the debate can be arranged from scratch in five minutes without ever making a personal revelation. This is no vox pop conducted on the street, when a reporter stops you and asks you how to spell your name. In this new, deeper anonymity, whether below the line or on social media, your identity is well protected even from the journalist who is quoting you.

Of course, this article was only the Guardian’s “Comments of the Day” roundup, not a major investigation. And of course, many arguments have been advanced about the benefits of anonymity in online forums – the speech tends to be freer and the focus stays for longer on the ideas, rather than the people propounding them. And of course, it’s not factually correct to say LearningIsLife said something when he or she didn’t. But still, the sense of strangeness doesn’t entirely dissipate.

Sometimes, assigning the wrong quotation to the wrong person does make a big difference to understanding, as in this example:

But the correction of attribution between upwthitimustput and LearningIsLife is something that could only really matter to the contributors, not the readers. The audience can hardly be any the wiser as to the authority of the comment, or more informed about its antecedents, if both the contributors concerned are anonymous. And it’s even slightly difficult to understand what’s in it for the commenters themselves: if you’ve opted for anonymity, what does it matter if someone gets your alias wrong?

Tags: anonymity, comments, corrections